Client communications

It is pleasant to imagine that once a creative professional “makes it”, everything comes naturally to them. We imagine that because someone is famous, or has a track record of producing great work (or books that sell) - they eventually reach a point after which each new project is a success. Their new ideas are welcomed based on their reputation alone.

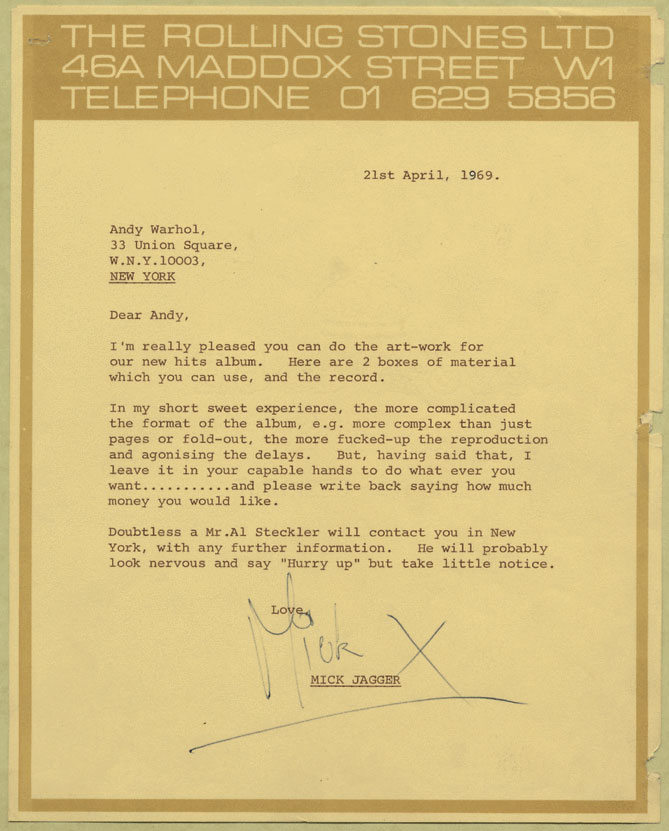

If all things turned out well in a creative career, we dream, our client communications would look something like this.

Letter from Mick Jagger to Andy Warhol, dated April 21, 1969: Collection of The Andy Warhol Museum

Reality is normally quite different. The letter from Mick Jagger to Andy Warhol is not an internet hoax. But it’s pretty much the only perfect-picture example I’ve seen. Here’s a client giving an artist (in this case, also designer) all needed materials upfront, full creative freedom, unlimited funds, and as much time as might be needed.

The Peacock Room by Smithsonian's Freer and Sackler Galleries.jpg)

In reality, even established, famous artists have to work to maintain client relationships. Expectations differ. So much is based on taste and aesthetic preference, that the potential for surprise is especially high in the creative professions.

The story behind James McNeill Whistler’s decorative treatment and mural in the Peacock Room (now in the Smithsonian’s permanent collection) is a perfect example of a client relationship gone wrong. To sum it up in business terms, the artist got so carried away making changes to a client project without notice or permission, that the entire project was threatened. The argument over whether the client should pay for the “surprise” masterpiece got so bad that it needed to be resolved in court. In the meantime, Whistler gained access to the room in question, and added a mural of a peacock squabbling over gold: an unkind, but memorable allegory on the client relationship.

We need clients. And constraints.

While client relationships can be difficult, design is best in collaboration between an expert in design, and a domain expert, the client. We find the best solutions when we apply our expertise to a real situation with real stakeholders. Working through assumptions, misunderstandings and finding the one solution that would satisfy the client is the way to better work.

And how would it feel to have no constraints on a project? Constraints can become a helpful set of scaffolding. Well-defined constraints help ensure success by limiting what we can change.

Working from Andy Warhol’s brief may seem great at first. But even the seemingly no-strings-attached approach is based on client communications (and maybe even disagreements) that have already happened. The client in this case knows what they will get because there’s a track record of matching expectations with awesome.

So, while it is my professional responsibility to avoid the situation in the Peacock room, I don't aspire to get the Warhol letter right away either. I’m only expecting it after years of putting in the work.