How to keep trying

Why do we get disappointed so quickly when trying new things?

I love trying new art supplies. A new art thing holds a promise of all the cool things I could potentially make with it. Now that I finally have the missing paint color (brush, Pencil, special paper, magic ink) - I can hope that making something awesome will be effortless from now on.

I often find reality disappointing. If I try out new materials by doodling aimlessly, and expect a masterpiece - or even any meaningful end result - I am setting myself up to fail. I get bored, stop rather quickly, and am unimpressed with results.

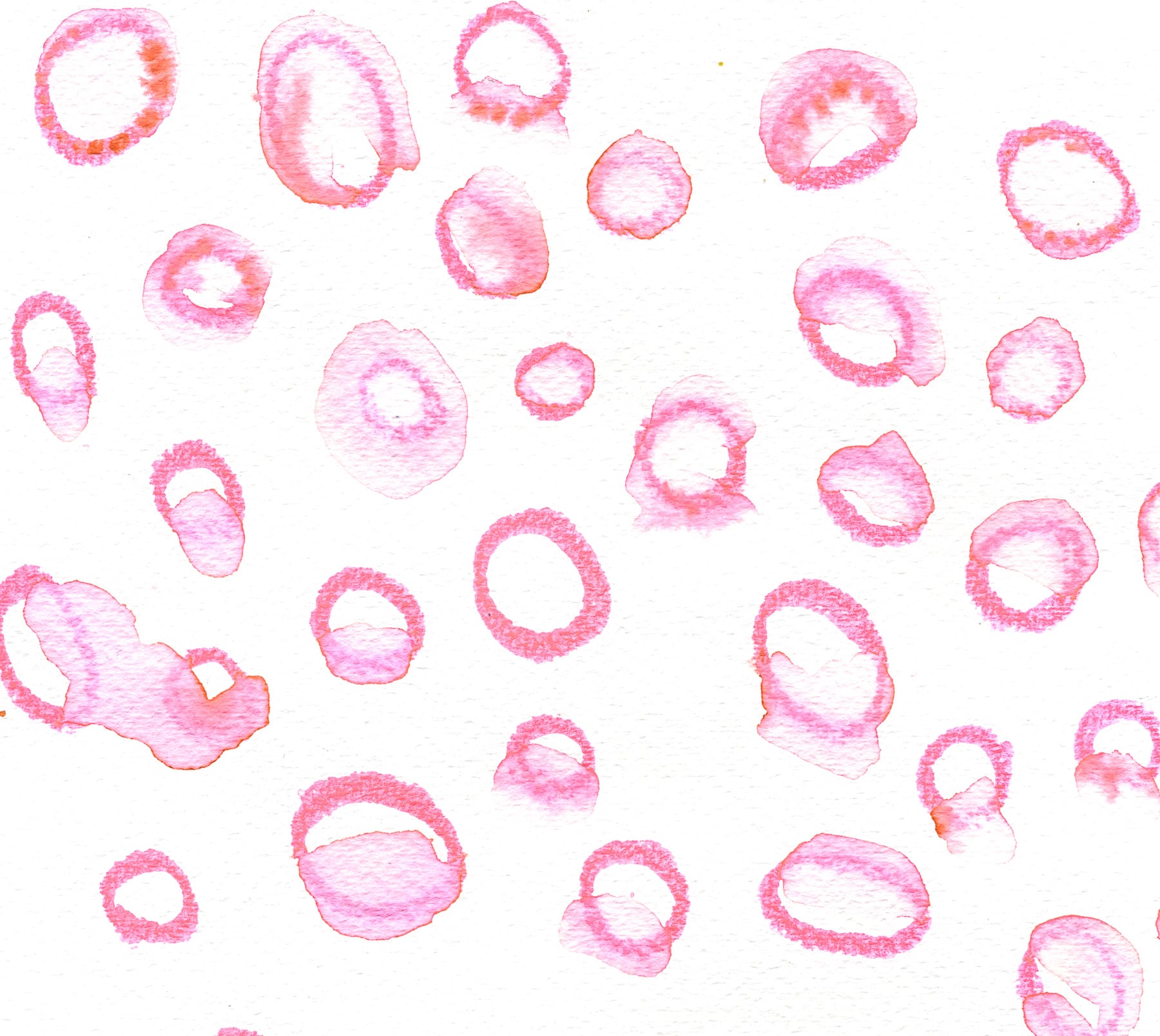

Here, I intentionally tried to "mess up" the marker lines with as much water as possible. With that objective in mind, the doodle is a success. Once things dried, I saw a pretty disruptive blob of ink, showing a lot of contrast with the original lines.

Do things on purpose

Playing with new materials can be so open ended that it becomes aimless. Of course, then I’d have to be very lucky to stumble into a beautiful solution by accident. Each material has its own habits. Aimless doodling with new materials often means that I choose the path of least resistance and let myself be guided by their quirky behavior. This is the opposite of purposeful exploration.

Purposefully exploring something, on the other hand, works pretty much every time I try it. There are four components to purposeful exploration. Having one or two of them figured out usually serves fine with quick, casual art or design exercises. For large projects, I make sure I’ve covered all four before I begin. The four things are constraints, problem, process and repetition.

1: Constraints

When the material itself does not offer enough challenges in handling, add some constraints on top. I imagine the process of making marbled paper leaves very little to chance. To have a passable, marbled looking result, you need to respect the chemical and physical processes that make the marbled look. There is little room for deviation. On the other hand, doodling with a marker on paper has little room for failure. A marker can work in many ways. So, I intentionally constrained myself to just making organic looking circles.

Constraints, like scaffolding, can guide creative decisions and help us get to interesting results.

2: A problem to solve

If there is no objective, then how do we judge what success looks like? Looking at my pink circles doodle halfway (it stared as a test with water-based marker on watercolor paper) I decided that I want a usable pattern for a background, and proceeded to make it look even and pattern-like.

Without a problem to solve, I couldn’t really judge whether the doodle was any good - aside from the rare case when something looks aesthetically amazing by accident. And I personally believe that to earn those accidentally amazing doodles (like Matisse!) we all have to work through many purposeful not-so-amazing preparatory doodles.

3: A modular process

Process is critical to getting better at anything. It makes it less likely that I’ll stop after trying something just a few times, or leave a project unfinished. With solid process, I always know what the next step is, and can move on even if my doodles are not looking great yet.

I almost stopped and gave up on this one halfway, but decided to finish anyhow and set it aside to dry. As a side benefit, I often like something I made quite bit better after I sleep on it.

4: Make many things

The idea of simply making more work has been a consistent presence in most books on creativity that I’ve read. Twyla Tharp, Austin Kleon, and Julia Cameron all say it works. A very cool friend recently dug up a story for me that perfectly illustrates this principle:

“The ceramics teacher announced on opening day that he was dividing the class into two groups. All those on the left side of the studio, he said, would be graded solely on the quantity of work they produced, all those on the right solely on its quality. His procedure was simple: on the final day of class he would bring in his bathroom scales and weigh the work of the “quantity” group: fifty pounds of pots rated an “A”, forty pounds a “B”, and so on. Those being graded on “quality”, however, needed to produce only one pot — albeit a perfect one — to get an “A”. Well, came grading time and a curious fact emerged: the works of highest quality were all produced by the group being graded for quantity. It seems that while the “quantity” group was busily churning out piles of work-and learning from their mistakes — the “quality” group had sat theorizing about perfection, and in the end had little more to show for their efforts than grandiose theories and a pile of dead clay.”

Excerpt From: David Bayles. “Art & Fear.”

Get the scaffolding in place, and free-flowing doodles will follow

In summary - set yourself up to enjoy the exploration you take on. Pick an objective, narrow down the materials and methods to just a few, follow a consistent process - and make many things! The simple trick to getting better through it all is to look at the results once in a while, see the bits you like, and do more of them.